Imagined vs. true constraints (and the wisdom to know the difference)

Core coaching philosophy #4

In this series of essays I’m going to outline the core philosophies that shape my thinking and approach to coaching. I will elaborate on why I believe these things to be both true and important, drawing on a wide range of sources and influence from the modern scientific, to the ancient spiritual. If there is one thing I’m confident of, it’s that my own thinking will continue to evolve over time. As it does so I will try to make updates to reflect that evolution. Whether you’re a client of mine or simply a passerby, I hope you find some food for thought here.I’m not a religious guy but I find a lot of wisdom in the words of the serenity prayer,

‘Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.’

In just a few words, it encapsulates a vital message about constraints that so many of us (myself included) are not great at living in accordance with. There are those very real constraints, namely time and control, that we ought to be accepting and yet we try our best to ignore or override. And there are those more changeable constraints, mostly the host of mental distortions about who we are and what we’re capable of, that we more readily accept, despite knowing that our mind is a poor reflection of the truth.

So we’re not all living a life in accordance with those words, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth striving for. A life that balanced acceptance and change would be a life well lived in my view. So here we are, trying to find the wisdom to spot the difference.

Accept the things I cannot change

Time

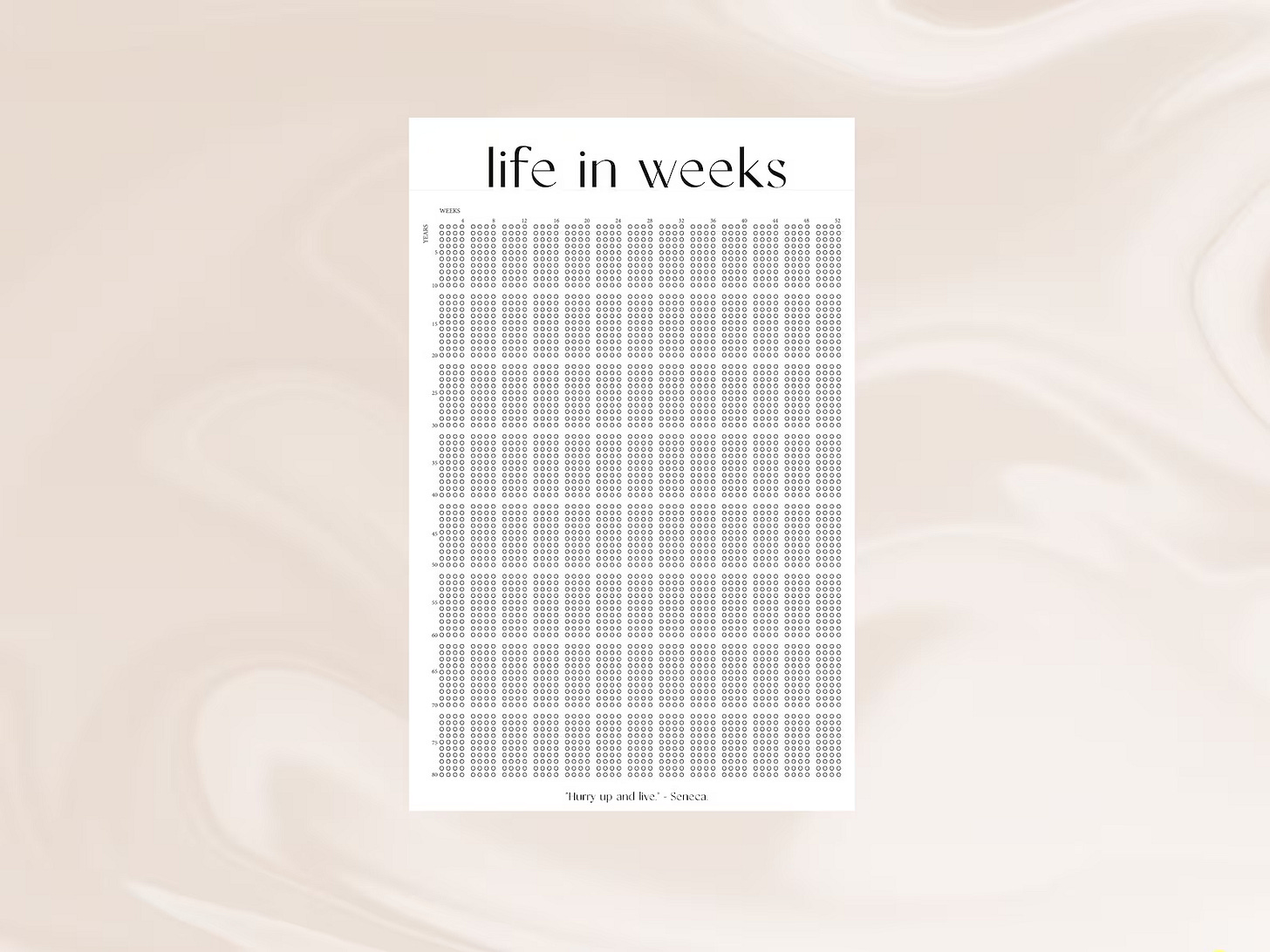

Time is the scariest constraint of all to embrace. It means facing up to the truth that one day we’ll die. Sounds morbid I know, but in his book ‘Four Thousand Weeks. Time management for mortals,’ Oliver Burkeman makes a compelling case for a more constraint-embracing way of living which breaks the collective self-delusion that we can simply continue to make better and better use of our time.

Of course technological advancements can shift the goalposts of what is possible. If the Silicon Valley guys injecting their children’s blood magically discover the elixir of life, then perhaps some of us will live meaningfully longer. And with the advent of AI, what one person can meaningfully get done will increase. But whether we live to 80 or 180; and whether we can get two tasks done in a day or ten, we’re still faced with the same dilemmas - life will never be truly long enough to do it all; and relentlessly pursuing productivity is a game that has no end - we’re like a dog chasing its tail.

So embracing the constraint of time, frames things differently. Rather than being a moment of despair, I think it plays an important role in being more purposeful with our lives. The Confucian quote, ‘We all have two lives and the second begins when we realize we only have one,’ rings true for me here. When we embrace the constraint of time, I think that’s when we start to live this second life, with a different emphasis to the first:

We meaningfully prioritise

We stop chasing our tail on productivity and face the facts of prioritisation. We make the tough choices about how we’re going to spend our time, and importantly, how we’re not going to spend it.

We’re reminded to try to live in the present

So much of our life is lived in a manner that projects into the future, and yet the only reality we ever have is the present. When the future arrives, it will do so in the form of the present. Embracing the constraints of time serves as an important reminder that if we’re not careful, we’ll spend an entire lifetime living for the future, which will never arrive.

‘People are like donkeys running after carrots that are hanging in front of their faces from sticks attached to their own collars. They are never here. They never get there. They are never alive.’ — Alan Watts

Control

As with time, I believe control is something that we have far less of than we think. But by contrast, the cutoff is less easily defined.

In the case of the tech industry, which is the primary domain in which I work, there are certainly those who would take exception to my assertion here. One only need to glance through Marc Andreesen’s Techno Optimist manifesto to get a sense of the man dominates universe and bends things to his will narrative that permeates parts of the industry.

But to my mind, the truth is that we live in (and are ourselves) inordinately complex systems, most of which we don’t understand, let alone control. And these complex systems call for a different mode of interaction. Dave Snowden’s Cynefin framework (pictured below) does a great job of outlining the different types of systems we exist in - clear, complex, chaotic and complicated - and the relevant decision-making strategies within those different systems. If we’re in a clear system, which is well understood with fixed constraints, then it lends itself to best practices - to simple rules that can be followed to get to good outcomes. But if we’re in fact in chaotic or complex systems (and I’d argue that most of the time we are) then Snowden proposes a more interactive way of making decisions, based on probing or acting upfront and then responding based on how the system responds to the initial action.

So acknowledging our limited control does not mean inaction. We don’t simply give up and get swept away by the current. But it does mean we stop pretending things are simple when they are in fact complex, and it allows us to live in a way that is adaptable, flexible and responsive, unburdened by the illusion of the control. Hopefully it also means we stop listening to dumb advice on Linkedin that pretends the world’s problems can be solving in five easy steps!

In the context of interpersonal relationships, this acknowledgement of our lack of control can be particularly freeing. Alfred Adler, the prominent psychologist, has a helpful concept around separation of tasks in which he makes a clear distinction between one’s own tasks and the tasks of others. When it comes to having a difficult conversation at work for example, your task might be delivering a particular message in a clear, calm and empathetic way. What’s NOT your task is how the other person responds - that’s their task. That doesn’t make it easy if they decide to blow up in response, but it serves as an important reminder of the bit that is actually in your control and therefore what you’re truly burdened with.

So, embracing our constraints around time and control allows us to be more purposeful, to prioritise, to be more present, and to unburden ourselves from false and ineffective strategies to wrestle control in the face of complexity. But where is it we need courage?

The courage to change the things I can

Self-imposed mental constraints

There is an endless list of names for the types of limiting beliefs and cognitive distortions which act as a self-imposed constraint - impostor syndrome, the inner critic, perfectionism, self sabotage, people pleasing etc.

They are all patterns of thinking and being that emerge through a combination of nature and nurture and can easily become ingrained in our sense of who we truly are. But going back to the first essay in this series, our mind is a poor reflection of the truth and as such, so many of these things which seem real and perhaps inevitable at the time, can and will change.

By calling them ‘self-imposed’ though, it might paint the picture that they are easy to change, and whilst there are examples of quick breakthroughs (you may even have experienced a sudden paradigm shift yourself), change is rarely quick or easy. For some of us it might even be a life’s work. But that work starts with the wisdom to tell the difference between these and the constraints of time and control; the courage to seek growth and change; and the long-term persistence to make it happen. Something I’ll discuss next.